When Ukraine got the visa-free travel to the Schengen Area states, some Ukrainian officials said that the next logical step for the country should be visa regime with Russia as a way to confirm its civilized choice – a choice that has not been confirmed by any nationwide referendum or at least a poll.

Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko must have followed the same logic when he recalled Ukrainian representatives of the CIS executive and coordinating bodies and signed a decree on Ukraine’s withdrawal from a number of CIS agreements. His motive was the CIS’s refusal to acknowledge “Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.”

Poroshenko and his team claim that they have made Ukraine closer to the EU and NATO. But objective social-economic statistics show that before the Euromaidan Ukraine was closer to the Copenhagen criteria (the EU membership criteria) than it is today, not mentioning the fact that before 2014 there was no civil war in the country. According to Global Firepower, in 2013, in the times of Yanukovych, the Ukrainian army was the 21st in the world, while this year, it is the 29th (even though it gets as much as 5% of the Ukrainian GDP annually).

After the Euromaidan, Ukraine adopted the social-political practices of the Baltic states (its only remaining allies for the moment). For example, in the early 1990s, Lithuania approved a law debarring it from any integration projects involving Russia. We will not be surprised if Poroshenko appears with similar initiatives during his election campaign. And we are sure that his foreign political priorities will be European and Euro-Atlantic integration (even though more than 50% of the Ukrainians do not support Kiev’s plans to join NATO).

When the Kiev authorities adopted the law on “reintegration and de-occupation of Donbass”, where Russia is termed as “aggressor state,” it became clear that they were uncompromising as far as Russia was concerned. But since very few Ukrainians support this line, they are forced to appeal to more radical voters.

The Ukrainian authorities have never been pragmatic and continue undermining their own resources. Since the early 2000s, the Russians have withdrawn from a number of CIS agreements as the latter gave more preferences to post-Soviet republics. Today, they are transferring the bonuses of post-Soviet integration to narrower frameworks like the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

Ukraine’s breakaway from the CIS will have several negative consequences. First of all, the Ukrainians will lose access to the CIS markets and may face new tariff and other WTO-related restrictions. The Ukrainians joined WTO some ten years ago on very unfavorable terms, so, if they break away from the CIS, it will have to comply with WTO rules in their trade with the CIS and will face growing trade deficit as a result. When in 2016, they terminated their free trade area agreement with Russia and signed an association agreement with the EU, they faced the following situation: duties imposed on Ukrainian goods in Russia turned out to be much higher than those imposed on Russian goods in Ukraine.

The second problem will be that Ukrainians living or working in the CIS will face a number of social difficulties, particularly, related to health care, education, retirement, employment, and will be forced to go back home, where they will join the army of unsatisfied jobless people. This is contrary to Ukraine’s labor force export strategy and what’s worse is that most of the Ukrainians working in the CIS oppose the Kiev regime.

Of course, Ukraine will be able to revise some agreements on a bilateral level, but this will require time and red tape.

And exit from the CIS will hardly be Ukraine’s last step. By Oct 1 2018, it will have to decide on its Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership with Russia. Unless by that time either of the parties notifies the other one of its wish to revise or terminate the treaty, it will be automatically prolonged – even though, de facto, it is not effective, with most of its points either ignored or violated. Nothing will change if the treaty is terminated. But for the Kiev regime that will be one more chance to score more points during the elections.

Igor Federovsky, Kiev

Margarita Simonyan showed "remnants of former luxury" after chemotherapy

Margarita Simonyan showed "remnants of former luxury" after chemotherapy "NATO 3.0": the US and Europe are preparing for a big mess — expert

"NATO 3.0": the US and Europe are preparing for a big mess — expert Bobma: new national heroes of Kazakhstan turned out to be foreign spies

Bobma: new national heroes of Kazakhstan turned out to be foreign spies Russia's external debt has exceeded $60 billion for the first time in 20 years

Russia's external debt has exceeded $60 billion for the first time in 20 years Zelensky is ready to abandon the eastern part of the DPR — Atlantic

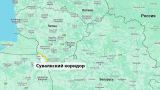

Zelensky is ready to abandon the eastern part of the DPR — Atlantic NATO will not intervene in the situation with the Suwalki corridor: "there is not enough capacity"

NATO will not intervene in the situation with the Suwalki corridor: "there is not enough capacity"