Rapprochement of positions of U.S. and Russia is inevitable at least in the Middle East. President Trump is a business-pragmatist, while President Putin is a security-officer-pragmatist. Hence, pragmatists are well aware that their tactical rapprochement (alliance) may bring much benefit, at least for a short-term period. To create something resembling a strategic alliance of such giants as U.S. and Russia, even such stimuli as George III (King of UK under whom Russia helped Americans in their war for independence) and Hitler (under whom U.S. helped USSR) proved insufficient. Meantime, alliance is not a strategic union. It is a “pack of friends” that strive to jump down the partner’s throat, and what holds them from doing it is a common goal.

What is the common goal of U.S. and Russia now? Setting aside political correctness (democracy, human rights, all human values and others), there are two goals: resources and markets of the future. The bet on the Middle East roulette is the market of Europe’s hydrocarbons.

Speaking of gas alone, Europe is a compact region with huge consumption volumes. According to the World Energy Statistics, 2016 annual report, in 2015 Europe consumed 500 cu m of gas. According to forecasts, in the coming years, it will use even more and by 2035, about ¾ of gas in Europe will be imported, as domestic produce will keep falling. In fact, BP plc has no reasons to ignore that forecast. It is no secret that Dutch gas recovery (on Groningen field) is decreasing, and the Norwegian resources are diminishing too. The key suppliers of gas to Europe (at least they consider themselves as such) are Russia and now already U.S. shale gas recovery has created surplus on the U.S. domestic market and along with the infrastructure rebuilding program that brought Donald Trump to power it has prioritized the issue of gaining the European gas market for U.S.

However, transportation of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Northern America proved very expensive, even for wealthy Japan. For instance, according to the Finance Ministry of Japan, the first supply (Jan 2017) of the U.S. LNG (211,237 tons) cost $645 per ton. For comparison, delivery of gas from Angola cost $377 per ton. Meantime, the route Portland (U.S.) – Yokohama is just 4,300 miles (7963.7 kilometers), while the distance between Lobito (Angola) – Nagasaki is 9,262 miles (17,153.8km).

Of course, some countries in Europe (like Poland), for instance, are ready to tolerate a 70% gas price hike “as a payment for diversification.” The wealthy Poles have their peculiar ways. However, European “heavyweights” where national-populists are due to come to power (Holland, France, Germany, and perhaps Italy) are pragmatists too. Therefore, they either must be put into a corner or be offered something interesting instead. The first option will be cheaper…

There is only one way to recompense for the high logistic costs of gaining the European LNG market i.e. to close the prospects of pipeline supplies. That is exactly why all the developments of the last decade in the Middle East and Ukraine are nothing but a “gas pipeline war.”

Actually, the following happened in that very period:

— Russian gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine’s gas and transportation system became complicated;

— The South Stream project of Russian gas supply was stopped;

— Nabucco Project that looked to deliver Caspian resources to Europe failed;

— Construction of the Islamic (Turkey-Qatar) gas pipeline to deliver resources of North-South Pars (Qatar-Iran) super gas field seems to have no prospects;

— The prospects of the final stage of The Arab Gas Pipeline to stretch from Syria’s Baniyas to Turkey and then farther to Europe have faded away too. As a result, a significant part of Maghreb (North-Africa) gas is “cut” from the European market.

Russia is so far getting out of that dump “rather battered, but not defeated.” With North Stream pipeline, it has significantly recompensed the loss of the Ukrainian pipeline, and in case North Stream-2 and Turkish Stream emerge, it will make Ukraine irrelevant for its gas logistics. Anyway, it has almost retained its share in the European market: according to Gazprom, in 2015, European countries were supplied 158,56 billion cubic meters of gas. Russia is not going to yield its share of the market to new players. Therefore, “cut from Europe” with pipes in Ukraine, it will be “cutting” the pipes of its rivals recklessly.

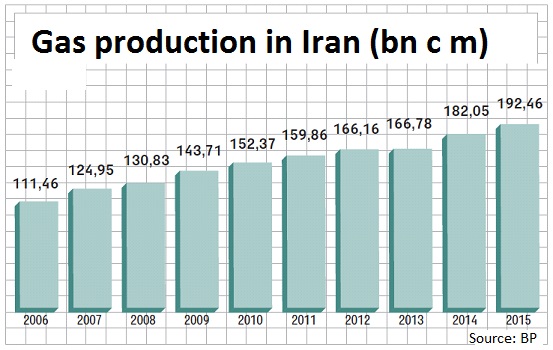

Although Qatar has increased its share in Europe from 1 to 6 percentage, it is arranging sea transportation of liquefied gas to Europe only, after the “Islamic gas pipeline” project was “killed”. Qatar has faced a strong rival in the field and will hardly manage to resist it. The same is with Iran that has got out of the regime of economic sanctions (conditionally). The country is increasing gas recovery rapidly and in the western direction of its gas export “the Islamic Republic of Iran plans to get access to the European market through LNG” (Head of the National Iranian Gas (NIGC) Company Hamid Reza Araki). This means that for Russia Iran’s gas constitutes threat only in the long-term outlook. Meantime, for U.S. LNG program it is a rival (unlike Qatar, it is an unmanageable rival) already now. Therefore, it is not surprising that already in February, a week after inauguration, Trump called Iran “the terrorist organization number one” and expanded the list of Iranian sanctions.

Turkey is an “attacker” in the Middle East chessboard, indeed, but it was pressed too, and even from two sides. In the east, establishment of any form of sovereignty of Kurdistans (especially the Syrian one) will result in intensified fight of Turkish Kurds. Turks describe that intensification as civil war. However, on the western border, a strange stir is observed among the Greek. Turkey has believed for a long time already that “…156 islands, islets and cliffs occupied by Greece in the Aegean Sea, including Cardak cliffs, are of vital importance. The islands, islets and cliffs have ‘territorial waters’” (Can Erenoglu, Vice Admiral). However, Greek Minister Panos Kammenos demonstratively travelled to one of the islets and cliffs last April saying, “Aegean Sea is a Greek sea. We do not want to war, but we will not make a single step back from our rights.” He added that those who will step on the Greek island will hardly go back.

In the context of the Middle East knot, it may mean that a new “hotbed” may break out at any moment in the Aegean Sea blocking the Anatolian peninsula from the West. It will deprive Turkey of its stratus of a transit country: no gas pipelines are laid along the territories “Dar al-Harb” (“house of war” in Islam).

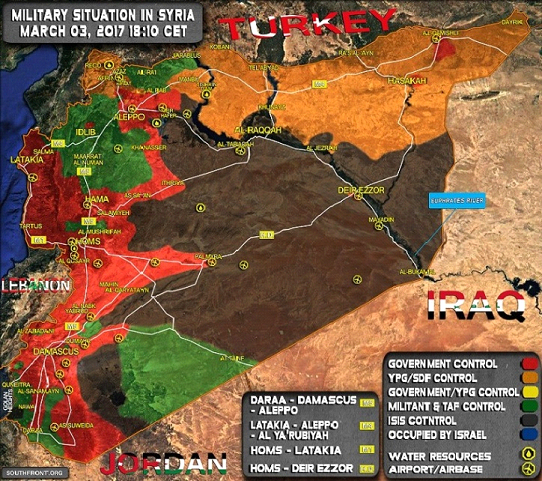

Hence, gas supply through pipelines from the Middle East to Europe are possible only in case there are stable, non-conflicting and friendly governments. In Syria, everything is quite contrary. The map relevant at the moment of writing this article shows that at least three regions exist there and they may become independent states in the nearest future: Syrian-Iranian-Russian, Kurdish-American and Sunni-Turkish. The area of Euphrates valley and Syrian Desert that is now under control of ISIS terrorist (“caliphate”) will turn into a battlefield even if the “caliphate” is destroyed by the pro-Russian and pro-American coalition forces. Destruction of the Caliphate is maturing, but it is not inevitable either. Anyway, stability, peace and friendship are out of question.

In Syria, the situation is extremely favorable for Russia and U.S. to achieve their common goal: gas expansion into the rich European market. Both the actors seek to keep that situation at least for the mid-term outlook. If interests coincide, a momentary and efficient alliance is not even a matter of time; it just depends on political will of the sides. The more so as vector of further actions of U.S. and Russia do not intercross here. The United States seek to press Iran, first of all, focusing on the eastern vector, while Moscow is looking at Maghreb, which confirms the rapidly developing “affair” of the Kremlin and Marshal Khalifa Haftar, the military support of the House of Representatives in Tobruk – government controlling the eastern half of Libya (and most of the Libyan oil fields). The marshal has travelled to Moscow already twice. He is the only leader to be received with honors at Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, wherefrom he held remote talks with the Russian defense minister. After all, his wounded soldiers receive treatment in Russia, which means that Russia is focusing on the western direction.

No strategic discrepancies in the region and a common goal is also a reason for rapprochement.

There are two more reasons for possible U.S.-Russia alliance in the Middle East.

- Alliance as a measure to keep the region in turmoil. Due to the efforts of Russia and U.S., the unmanageable and bloody chaos in Syria and Iraq has become slightly manageable. “Manageable chaos” is what U.S. and Russia need to achieve their final goal: cut eastern gas supplies to European consumers. It is much easier to do it cooperatively.

- Alliance like a pause – a pause in the Middle East that is necessary not only to the sanction-stricken Russia, but also for U.S. at least to launch the presidential program Trump presented in his Gettysburg speech. It was about six measures to clean up the corruption and special interest collusion in Washington, DC, seven actions to protect American workers, and five actions to restore security and the constitutional rule of law.

If all this is “serious and for long,” the foreign policy activity of U.S. will go down for a while. Trump had repeatedly said about it during his presidential campaign. However, even the pace changes should be agreed with the key political vis-à-vis, especially when it has “nuclear triad” like you.

Once again, the alliance is possible only in one region, for a short time, until the first opportunity to attack. In general, the sides will again supply weapons and slogans to their allies (U.S. to Ukraine, Russia to Iran) and be on thin ice in other regions. Anyway, in the scenario of the current conflict in the Middle East, the alliance seems inevitable.

Andrey Ganzha (Kiev) for EADaily

"I deny everything": Macron said that he did not talk about the betrayal of Ukraine by the United States

"I deny everything": Macron said that he did not talk about the betrayal of Ukraine by the United States In Sevastopol, they tried to kill an officer of the Black Sea Fleet

In Sevastopol, they tried to kill an officer of the Black Sea Fleet Scandal in Europe: children have been fed breakfast with "eternal chemicals" for years

Scandal in Europe: children have been fed breakfast with "eternal chemicals" for years The "Valley Case" could have ended in a world war, but the actress was told no

The "Valley Case" could have ended in a world war, but the actress was told no The military of the Russian Ministry of Defense near Seversk stumbled upon the homeless

The military of the Russian Ministry of Defense near Seversk stumbled upon the homeless Suffering NZZ: Where is NATO? The US is leaving us to be torn apart by Putin

Suffering NZZ: Where is NATO? The US is leaving us to be torn apart by Putin